On the 28 October, 1916, Australians were asked to vote YES or NO in favour of, or against, military conscription.

The voting paper had only one question:

Are you in favour of the Government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the term of this war, outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service within the Commonwealth.YES or NO?

Many did not understand the wording.

Both sides mounted vehement campaigns, some scurrilous.

-------oOo-------

It should be noted that whilst all of the historical documentation refers to the ballot as a "referendum", it was not such in fact: it did not involve a proposal to amend the Constitution of Australia and therefore it had no legal force, it did not require approval in a majority of states, and residents of federal territories were able to vote.

-------oOo-------

Prime Minister Billy Hughes was aggressively in favour of conscription of young Australian men for overseas service during World War I. Although the Australian government already had powers sufficient to introduce overseas conscription, due to the controversial nature of conscription and a lack of clear parliamentary support, Hughes took the issue to a public vote to obtain symbolic, rather than legal, approval for the move.

The Yes vote appeared likely to be successful, with Hughes campaigning widely and often.

-------oOo-------

Opposition to conscription came from various bodies and for various reasons:

- That it was immoral to compel men to kill other men.

- That any military service should be voluntary.

- From trade unions fearful that the absence of men overseas would result in foreign workers carrying out their jobs in Australia.

Much of the propaganda against conscription sought to play upon the fears of several sections of the community – women would lose their sons and spouses, farmers' fields would fall fallow without sufficient labour, and workers would be replaced by cheap foreign labour in their absence.

-------oOo-------

Just about every influential public man in Australia supported the conscription campaign. All non-Catholic church heads published in support of the movement, as well as the Salvation Army, the newspapers, and many jurists. Upon the announcement of the campaign and the vote, most media outlets quickly took up the cause, with Norman Lindsay and David Low producing some of the most powerful images of the war with their posters in support of the 'yes' vote.

-------oOo-------

Anticipating that the referendum would pass, and desiring that as many men as possible be readied for service following its passage, Hughes issued a directive that severely undermined his popularity. Using pre-existing powers under the Defence Act, Hughes ordered all eligible men between 21 and 35 to report for military duty, to be examined for medical fitness, and then go into training camp. Exemption courts could grant a leave to individuals based on specified criteria such as ill-fitness, employment in certain industries, or conscientious objection. The Governor-General approved the declaration, and the call-up was announced, with all eligible men compelled to report.

One significant aspect of this measure was the compulsory fingerprinting of all those called up for enlistment. The reason was valid enough – there were problems with exemption certificates being fraudulently produced, or valid certificates being sold or reused by other individuals and fingerprinting was thought to be a solution to this problem. However, there was significant public backlash from this "October Surprise". The use of fingerprinting was almost solely associated with criminal activity and investigation, and was unnecessarily heavy-handed. Many resented this pre-emptive measure by Hughes, viewing it as an arrogant assumption about the result of the forthcoming vote.

Until that point, all indications seemed to favour a victory for the "Yes" vote, but thereafter, the momentum swung steadily towards 'No'.

On 25 October, 3 days before the plebiscite, at a meeting of the Commonwealth Executive Council, issued another decree. Although the meeting was poorly attended, Hughes tabled a proposal to authorise returning officers on polling day to ask voters who were men between ages 21 and 35 whether they had evaded the call-up and if they were in fact authorised to vote. If their answer was not satisfactory, their votes were not counted.

The proclamation of this new regulation was to be delayed until the very last possible moment before the poll but it was leaked and became public.

Hughes seems to have been completely unaware of how high-handed such an edict appeared to his fellow Cabinet members. The Executive Council rejected the proposal on that occasion. On 27 October, Hughes reconvened the Council, with the Governor-General present, and the Council approved the motion, although the Governor-General was not told about the rejection of the same proposal two days earlier. The edict was published in the Government Gazette that evening.

The fallout was swift. The edict became public and the government was threatened with collapse, with four of the nine members of the First Hughes Ministry having quit. The publicity about Hughes's peremptory move and its consequences was a disaster, coming on the eve of the poll. Hughes, distraught and overwrought, called the Governor-General at midnight, saying he had no one else to talk to.

The No vote won a close contest, Hughes was expelled from the Union movement and his Labour Party membership was revoked. He remained defiant to the end. It was everyone else’s fault. Socialists, pacifists, Irish Catholics, saying “I did not leave the Labour Party. The Party left me.”

-------oOo-------

Hughes took what was left of his political support and joined the Conservatives. He formed a Nationalist coalition and won the 1917 election. Despite this he lost the 2nd Conscription plebiscite (by a larger majority, on the 20th December, 1917.)

-------oOo-------

By the way:

William “Billy” Morris Hughes (1862 – 1952), was an Australian politician who served as the 7th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but his influence on national politics spanned several decades. Hughes was a member of federal parliament from Federation in 1901 until his death, the only person to have served for more than 50 years. He represented six political parties during his career, leading five, outlasting four, and being expelled from three.

At the age of 90 years, one month and three days, Hughes is the oldest person ever to have been a member of the Australian parliament. He had been a member of the House of Representatives for 51 years and seven months, beginning his service in the reign of Queen Victoria and ending it in the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. Including his service in the New South Wales colonial parliament before that, Hughes had spent a total of 58 years as an MP, and had never lost an election. His period of service remains a record in Australia. He was the last member of the original Australian Parliament elected in 1901 still serving in Parliament when he died.

-------oOo-------

Gallery:

Ballot paper

Anti-Hughes poster

‘The New Southern Cross’ by Claude Marquet

Norman Lindsay pro-conscription poster

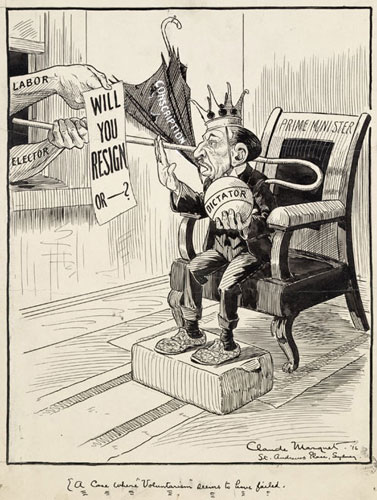

Cartoon of Billy Hughes after the failed plebiscite, 1916, by Claude Marquet

Leaflet bearing a verse by W.R. Winspear and a cartoon by Claude Marquet, featuring an image a deeply worried woman casting a ‘Yes’ vote while Billy Hughes, Australia’s Labor prime minister and supporter of conscription, looks on gleefully.

-------oOo-------

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.